Exploring Environmental Justice in a High School Classroom

In a city as diverse as New York, neighborhood wealth disparities transform into issues of environmental justice—from lack of access to green spaces to increased pollution. Collaborating with the Secondary School Field Research Program at the Earth Institute, nine PhD students from the Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology (E3B) department spent the past year developing a six-week program to work with young scientists experiencing these environmental issues firsthand. With the help of a Public Outreach Grant from the Center for Science and Society, these students created and facilitated the Environmental Justice and Urban Ecology Summer Research Program for high school students from the Washington Heights Expeditionary Learning School (WHEELS).

One of the organizers, Roi Ankori-Karlinsky (Graduate Student; Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology) as well as two undergraduates who worked with the high school students on a day-to-day basis over the summer, Moshab Rahman (Columbia College, ‘23) and Jada Tulloch (Columbia College ‘24), sat down with our work-study student Ariana Novo to discuss the project.

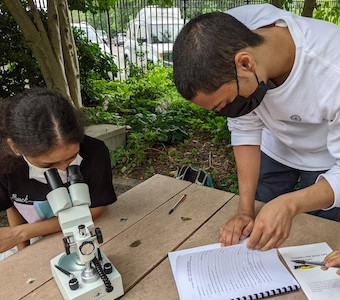

Collaborating with Jared Fox, an environmental and climate science teacher at WHEELS, and Génesis Abreu, the Youth Environmental Program Manager at Friends of WHEELS, a nonprofit supporting the high school, the organizers of the summer research program were connected to students who had been working on their own environmental biology-based endeavor, the Clean Air Green Corridors Project, combating the unequal access to green spaces near their school. The high school students formulated their own research questions and collected data related to their projects including the amount of shade produced by different trees, areas of higher biodiversity, and water quality in the Harlem River. “Everything we measured and everything we set out to answer was based on [the students’] own interest in environmental justice and the Green Corridors Project,” said Ankori-Karlinsky. Rahman and Tulloch described how they split the daily activities of the program, teaching both conceptual scientific knowledge such as historic redlining in the neighborhood and environmental justice terminology as well as applied field research methods such as vegetation and water monitoring. At the heart of it all was advocacy as Tulloch noted, “one of the main themes of the program is talking about how we impact the environment but also how the environment impacts us.” Rahman added, “learning about how to translate science into advocacy was an ongoing process for us as peer mentors.” Collecting data allowed the students to quantitatively examine their research questions, but it was the program’s connection to the students’ personal experience that gave this information the potential to promote change. The students had varied interests, from science and engineering, to journalism, the humanities, and community activism. This diversity of experience and disciplines allowed students to bring their own perspectives to the worktable. As Rahman noted, “everybody does have something to learn from everyone else.”

Tulloch added that “a part of environmental justice is ensuring that everyone has the right to live safely and healthily … and the common denominator here was that they all lived in this community and they all grew up experiencing some of the injustices that we talked about.” One example of this was when they were collecting bacteria samples from the Harlem River: “[the students] can see what [they’ve] been told for so many years. Don’t go in the water. It’s not safe. And we can actually see the results of the bacteria that made it unsafe.” The data set collected in the summer of 2021 will be used by future science classes and the Clean Air Green Corridors Project at the high school. The students also presented their research findings on soil, air, and water quality and their recommendations for how to advocate for environmental justice, restoration, and reclamation in their neighborhood during a virtual community forum in August.

Ankori-Karlinsky expressed his hopes for the program to expand in future summers with growing partnerships with WHEELS and other community organizations. “We’re starting to get newer PhD students involved in planning, potentially creating this as a summer course that PhD students run,” he added. As the coordinators look towards next summer, Tulloch and Rahman spoke of their positive experiences working in the Environmental Justice and Urban Ecology Summer Research Program. “It was so amazing to be able to watch the students grow and watch each other grow … and be able to connect with each other for this passion for environmentalism and learning and experiencing the things that we all deserve to experience,” said Tulloch.

To learn more about interdisciplinary programs supported by the Center, visit our page on public outreach grants. If you are interested in participating in the Environmental Justice and Urban Ecology Summer Research Program next summer, contact Roi Ankori-Karlinsky.